Guide: Nissan R32 Skyline GT-R - a Historical & Technical Appraisal

/BACKGROUND

When Nissan introduced the R32 Skyline in 1989, they also decided to revive the Gran Turismo Racer (GT-R).

It had been 16 years since a Skyline GT-R was last offered; the unsuccessful second generation KPGC110 of 1973 had shifted a mere 197 units.

By comparison, the R32 variant was a massive commercial success. Nearly 44,000 of these third generation GT-Rs were produced between August 1989 and November 1994.

Nissan never imagined the new model would prove as popular as it did.

The original plan was to build 5000 examples in order to homologate the R32 GT-R for Group A racing.

However, demand far exceeded supply and Nissan decided to allow an unlimited production run.

Making these sales figures even more impressive was the fact that the GT-R was only officially available in Japan. Nissan did send 100 cars to Australia, but never offered it in Europe and it wasn’t even legal for sale in the USA.

At the time, Group A touring car racing was dominated by the Ford Sierra Cosworth and BMW E30 M3. Nissan wanted a more competitive vehicle to replace the R31 GTS-R and decided to produce a machine for the 4.5-litre class that was capable of outright victories.

What they created was among the most technologically advanced machines of its time.

The R32 GT-R was equipped with four-wheel drive, four-wheel steering and bristled with electronic management systems. In racing tune, its twin turbocharged straight six engine could produce enormous power and Nissan went on to dominate Group A touring car racing for the next few years.

Production started on 24th August 1989.

CHASSIS

The E-BNR32 unitary steel chassis came with independent suspension all round.

At the front were double wishbones with a third link at the outer end of the upper wishbone. A multi-link arrangement was used at the rear. Stiffer than normal coil spring / damper units were installed at each corner along with anti-roll bars at either end.

A sophisticated four-wheel steering system was called Super HICAS (High Capacity Actively Controlled Steering). It allowed the rear wheels to steer a maximum of one degree making the car feel more nimble and improving stability. The rear wheels could turn in either the same or opposite direction to the fronts which also assisted low speed manoeuvrability.

Ventilated brake discs measured 297mm at the front and 296mm at the rear. They came with four and two-piston calipers respectively.

The 8 x 16-inch five spoke alloy wheels originally came shod with Bridgestone Potenza tyres.

A 72-litre fuel tank was located in the boot floor.

ENGINE / TRANSMISSION

The longitudinally mounted straight six engine was developed at Nissan Kohki (Nissan’s power train engineering and manufacturing facility).

A twin turbocharged 2.4-litre version of the RB25 engine was originally considered. With the 1.7 Group A multiplier for turbocharged engines, this would have put the car in the four-litre class with a 10-inch wide wheel limit.

However, the 100kg weight of the four-wheel drive system meant the GT-R would have been at a disadvantage to other cars in its class.

Nissan therefore opted for a 2.6-litre displacement and put the GT-R in the top flight 4.5-litre class where 11-inch wide tyres were permitted.

A new cast-iron engine block with light alloy four-valve head was developed to suit the increased capacity.

Designated RB26DETT, this engine displaced 2568cc thanks to a bore and stroke of 86mm and 73.7mm respectively.

It had dual overhead camshafts and ran wet-sump lubrication.

Two Garrett T28 ceramic turbochargers were installed along with an air-to-air intercooler. The ceramic route was taken as it offered better heat resistance than standard steel turbo rotors.

Compression was 8.5:1 and a custom multipoint fuel-injection system was developed.

At the time, Japanese manufacturers had a gentleman’s agreement that limited engines to 276bhp in order to avoid a horsepower war. The R32 GT-R officially developed 276bhp at 6800rpm. However, the true horsepower rating was 313bhp at 6800rpm.

Peak torque was 260lb-ft at 4400rpm.

Transmission was via the ATTESSA E-TS permanent four-wheel drive system, a five-speed manual gearbox, multi-plate hydraulic clutch and limited-slip differential.

Nissan developed the torque-sensitive electronic four-wheel drive system specially for the R32 GT-R. Branded ATTESSA E-TS (Advanced Total Traction Engineering System for All Terrain – Electronic), it used a microprocessor to sense lateral G, throttle opening and engine speed. Upon sensing oversteer or broken traction at the rear, it sent torque the rear wheels couldn’t handle up to the front axle.

This data was also fed to the anti-lock brake system (ABS) which measured wheel speed and longitudinal G force.

BODYWORK

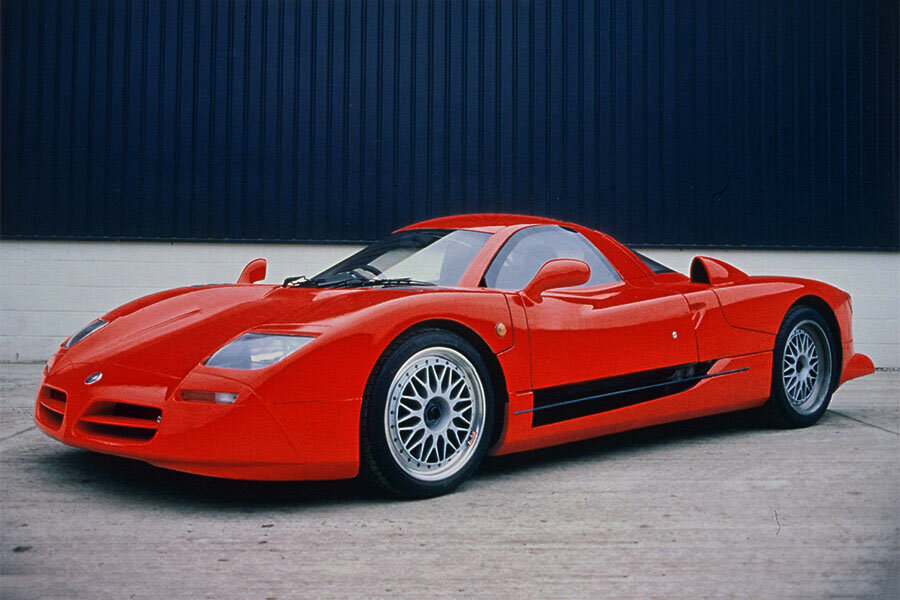

Visually, the GT-R was given a number of enhancements over standard R32 Skylines.

The front bumper was redesigned. It housed a deep front spoiler, brake cooling ducts and an enlarged intake for the radiator.

Another intake was located between the new ellipsoidal headlights. The shorter bonnet (like the front fenders) was now formed in lightweight aluminium.

Body coloured side skirts were installed along with a bigger rear spoiler.

Colours were limited to Gun Grey Metallic, Crystal White, Black Pearl Metallic, Spark Silver Metallic and Greyish Blue Pearl.

INTERIOR

Changes were also made to the interior, but like most Japanese cars of this era, there was an abundance of hard plastic in the cockpit.

Special GT-R equipment included high-backed sports seats trimmed in dark grey fabric, a three-spoke steering wheel with leather rim and a leather gear knob.

The main instrument binnacle housed large read outs for road and engine speed. To the right were smaller gauges for oil pressure and water temperature. To the left was a small fuel level indicator and a torque split gauge that showed how much power was being sent to the front diff.

A bank of three extra gauges were located on the centre console: an ammeter, oil temperature gauge and boost read out.

Air-conditioning was standard along with electric windows.

WEIGHT / PERFORMANCE

The GT-R weighed in at 1430kg and had its top speed artificially limited to 112mph (180kph). Its true top speed was 165mph and 0-62mph took 5.6 seconds.

PRODUCTION CHANGES

In late 1991, a series of changes were made to the GT-R.

Side impact protection bars were added that resulted in a 50kg weight increase. The headlight projectors were also modified, the oil pump drive was widened and the cylinder head was modified for lightness and strength.

AUSTRALIAN VERSION

Between April and June of 1991, 100 GT-Rs were built for the Australian market.

These export cars came with a host of minor modifications to include different lights, badges, instrumentation, switchgear, upholstery and wiring. However, no major alterations were made to the base specification.

R32 SKYLINE GT-R V-SPEC

To celebrate the GT-R’s success in competition, a V-spec package was made available from January 3rd 1993.

Bigger brake discs were added (324mm front and 300mm rear) along with a bigger brake master cylinder, uprated Brembo calipers and 17-inch BBS wheels.

R32 SKYLINE GT-R V-SPEC II

On February 14th 1994, the original V-spec was replaced by the V-spec II package.

Nissan added a retuned ATTESA E-TS system and wider tyres (245/45 R17 instead of 225/45 R17).

END OF PRODUCTION

Production ceased in November 1994, by which time 43,810 standard GT-Rs had been completed (including 100 Australian-market examples).

Nissan had also produced two special variants not included in this total (covered in detail separately).

First came the Nismo (RA) which was an Evolution model of which 560 were built between December 1989 and March 1990. 500 were required for homologation and the additional 60 were turned into racers.

This was followed in July 1991 by the Nismo N1 (ZN) which was designed for home market N1 racing. 245 were built.

Text copyright: Supercar Nostalgia

Photo copyright: Nissan - https://www.nissan-global.com