Guide: Nissan R390 / 97 - a Historical & Technical Appraisal

/BACKGROUND

At the end of the 1992 season, Nissan withdrew from sports car racing.

A Group C programme that began in 1985 had produced a series of spectacular vehicles and culminated with Nissan winning the 1990, 1991 and 1992 All Japan Sports Prototype Championships.

In conjunction with their official North American motorsport partner, Electramotive Engineering, Nissan had also won the IMSA GTP championship for three consecutive seasons in 1989, 1990 and 1991.

Against the might of Porsche, Jaguar and Mercedes-Benz, success at Le Mans had proven elusive though.

Like domestic rivals, Toyota and Mazda, Nissan were desperate to win the fabled 24 hour race, but despite a big budget and top drivers, the firm’s best result was fifth overall in 1990.

Between 1991 and 1994, Nissan did not race at Le Mans.

They returned in 1995 with the GT1-class R33 Skyline GT-R LM. Compared to the McLaren F1 GTR and Ferrari F40 GTE, the Skyline was well off the pace, but a tenth place finish overall was still impressive.

By 1996, the Skylines were further behind and, with the advent of the rule-bending Porsche 911 GT1, Nissan knew they would have to produce a purpose-built racing car.

Like Porsche, Nissan would exploit a GT1 loophole that stipulated just one road car had to be produced to secure homologation.

Porsche had initially gone against the spirit of the regulations in 1994 with the Dauer 962 LM Sport which was banned from competing in 1995. For 1996, they created the 911 GT1 which, unlike a McLaren F1 or Ferrari F40, was clearly never intended as a genuine series production model.

Nevertheless, the rule makers proved powerless and thus began an arms race that, by the end of the decade, had destroyed the promising GT1 category.

Mercedes-Benz followed Porsche’s lead with the even more extreme CLK GTR after which Nissan released their own GT1 challenger: the R390.

Built solely for Le Mans, the Japanese car would not participate in the inaugural FIA GT Championship that replaced the BPR GT series for 1997.

The R390 was developed in England by Tom Walkinshaw Racing (TWR).

TWR had been responsible for the Jaguar sports car operation between 1984 and 1992. This had garnered Le Mans victories in 1988 and 1990 plus multiple World and IMSA championships.

The TWR-designed and Joest-run Porsche WSC-95 had also won Le Mans in 1996, so it was easy to understand why Nissan wanted to partner with the English firm.

In September 1996, Nissan president, Yoshikazu Hanawa, signed a two-year agreement that would see the R390 contest the 1997 and 1998 Le Mans 24 Hour races.

Although Nissan did not harbour any aspiration to series produce the R390, the new model was originally built as a road car with the racing version developed afterwards.

A price of $1m was routinely quoted for the R390 street version, but only one example was ever built.

CHASSIS

To save time and money, TWR based the R390 around a modified carbonfibre monocoque from the Jaguar XJR-15.

TWR had created the XJR-15 in 1991 as a wickedly expensive road-going version of the Le Mans-winning XJR-9. 53 were built, each costing £500,000. XJR-15 owners were able to enter their cars in spectacular one-make racing series that supported several Formula 1 races in 1991.

Lower, wider and shorter than the XJR-15, the R390 also had a 2mm longer wheelbase (2720mm).

Suspension was via double wishbones at all four corners plus inboard shocks and coil springs. Anti-roll bars were installed at either end.

Spring rates in the road-going version were significantly softer than the racer and the ride height was raised by about an inch.

AP Racing supplied the ventilated 14-inch carbon brake discs and the six piston calipers. A specially designed ABS system was installed along with switchable traction control and non power-assisted rack-and-pinion steering.

The centre-lock BBS wheels on the road car measured 18 x 8-inches at the front and 19 x 10.5-inches at the rear.

For the racing version, these were switched to 11 x 18 at the front and 13 x 18 at the rear.

Both variants used Bridgestone tyres.

ENGINE / TRANSMISSION

Like its recycled chassis, the R390’s engine was also heavily derived from existing components.

Whereas the Skyline GTR-LM of 1995 and 1996 had used the RB26DETT straight six engine, its iron block and high centre of gravity made it unsuitable for the R390.

Instead, Nissan and TWR chose to resurrect the VRH35Z engine from the Group C programme.

This was a twin turbocharged DOHC 3.5-litre 90° V8 with light alloy four valve heads, a magnesium alloy block and lower centre of gravity. It was also better suited to being used as a stressed member.

The R390 variant was designated VRH35L.

Displacement was 3495cc thanks to a bore and stroke of 85mm and 77mm respectively.

The revamped engine ran a 9.0:1 compression ratio with electronic fuel-injection and two IHI turbochargers.

In racing trim (with the mandatory GT1 air restrictors in place), it produced 641bhp at 6800rpm.

This was de-tuned to 550bhp at 6800rpm for the road car which had a torque rating of 470lb-ft at 4400rpm.

Both variants used a transversely mounted Xtrac six-speed sequential gearbox and limited-slip differential.

BODYWORK

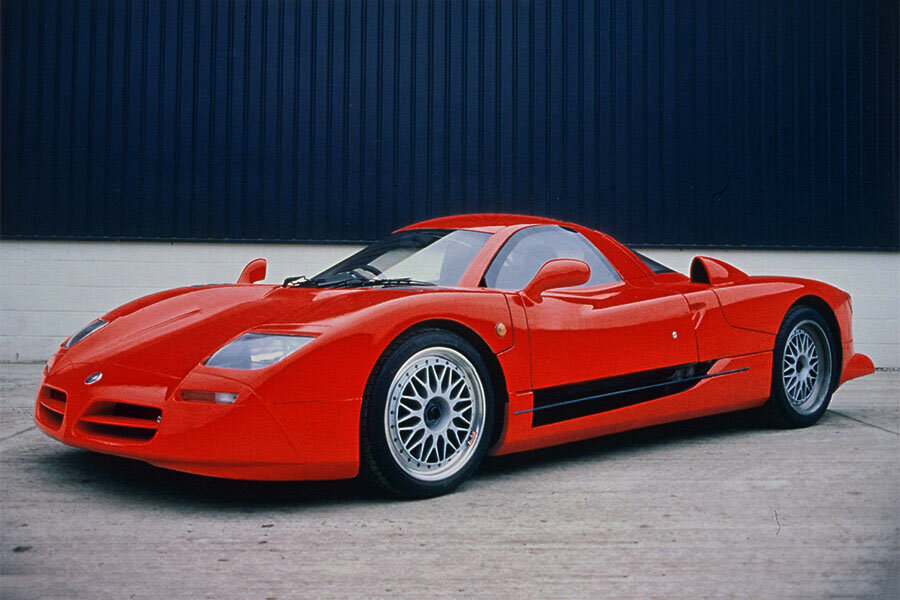

The R390 styling group was led by Ian Callum of TWR.

The only Nissan parts used were headlights from the 300 ZX.

There were inevitable similarities between the new car and the Jaguar XJR-15, particularly around the cockpit profile and rear deck.

Of all the GT1 specials manufactured between 1996 and 1998, the Nissan R390 was perhaps the most conservative looking. It had neither the drama of an Italian thoroughbred nor the resolve of a Porsche or Mercedes-Benz.

Two air intakes were carved out from the nose and a single cooling scoop was mounted on the shoulder of each rear wing. There was also a bank of vents located above each front wheelarch to reduce air pressure.

Otherwise, the R390 was remarkably devoid of elaborate cooling solutions when compared to its rivals.

One of the R390’s most distinctive features was its sloping tail, above which, a discrete full width rear wing was mounted.

For the racing version, the road car’s rear spoiler was discarded in favour of much bigger wing mounted on two central pylons. Additionally, the front apron was re-profiled and two supplementary spot lights for night driving were installed. The ride height was dropped and firmer spring rates adopted. A bigger rear diffuser was also fitted. Two large cooling ducts were cut from the sills ahead of each rear wheel and smaller wing mirrors were used.

INTERIOR

Whereas the tiny cockpit on the road version was equipped with leather bucket seats, an upholstered dash and carpeted floors, all this was stripped away for the race car.

Analogue instruments were switched to digital for track use.

Both road and race variants were right-hand drive with a right-hand gear shift.

EARLY TESTING

In the middle of March 1997, a remarkable four months after the project was signed off, TWR began testing at Estoril.

Over 2000 miles were completed in Portugal by Martin Brundle, Erik Comas and Jorg Muller.

ROAD VERSION LAUNCH

One week later, the road version was unveiled in Paris.

Painted red and UK registered P835 GUD, a top speed of 220mph was quoted for the 1098kg machine.

0-62mph required 3.9 seconds.

FURTHER TESTING

By the middle of April, a trio of racing R390s were ready to be trucked down to southern France for a four-day test at Paul Ricard.

Two of the cars were finished at the track and a contingent of nine drivers was present.

After a final shakedown at Silverstone, it was time for Le Mans Pre-Qualifying.

1997 LE MANS PRE-QUALIFYING

Pre Qualifying took place over the weekend of May 3rd and 4th.

Chassis R1 was on hand for Riccardo Patrese, Aguri Suzuki and Eric van de Poele, chassis R2 for Erik Comas and Kazuyoshi Hoshino and chassis R4 for Martin Brundle and Jorg Muller.

Brundle set the fastest overall time of the weekend. The newly re-bodied Porsche 911 GT1 was second, although both cars would probably have been behind the Joest-run Porsche WSC-95 had it not been plagued by gearbox problems.

As for the other two R390s, Comas / Hoshino went twelfth quickest while the Patrese / Suzuki / van de Poele entry was 17th.

Unfortunately, the weekend was overshadowed by the death of French rising star, Sebastien Enjolras.

On Saturday, the rear bodywork of his open-topped WR Peugeot had detached itself through the fast left hand kink after Arnage corner which launched the car ten metres into the air.

Landing upside down and bursting into flames upon contact with the guard rail, Enjolras suffered a major head trauma and was killed instantly.

It was the first fatal accident at the Le Mans circuit since Jo Gartner’s death in 1986.

SCRUTINEERING PROBLEMS & SUBSEQUENT MODIFICATIONS

Despite the R390’s promise at pre-qualifying, Nissan had been permitted to run having technically failed scrutineering.

The problem was that TWR had not properly incorporated the mandatory 125-litres of air-tight luggage space required by the GT1 regulations.

To race at the 24 Hours in June, the R390 would have to be modified to increase its luggage capacity.

To accomplish this, TWR re-routed the exhaust system, but the lack of another pre-race endurance test failed to reveal the problems this would cause…

1997 LE MANS 24 HOURS

The 1997 Le Mans 24 Hours was held over June 14th and 15th.

A team of three R390s was sent to Le Mans: chassis R1 for Eric van de Poele, Aguri Suzuki and Riccardo Patrese, chassis R2 for Kazuyoshi Hoshino, Erik Comas and Masahiko Kageyama and chassis R4 for Martin Brundle, Jorg Muller and Wayne Taylor.

Qualifying saw the TWR-built 1996 Le Mans-winning Porsche WSC-95 run by the Joest team take pole.

Next up was one of the works Porsche 911 GT1s followed by the Moretti Racing Ferrari 333 SP in third.

Best of the R390s was chassis R1 of van de Poele / Suzuki / Patrese which posted fourth quickest time.

R4 was twelfth (Brundle / Muller / Taylor) and R2 was 21st (Hoshino / Comas / Kageyama).

In the race, Eric van de Poele briefly led the opening stages, but thereafter, the event proved a major disappointment for Nissan and TWR.

At the end of the second hour, Brundle came into the pits for a clutch change, however, it was the fourth hour that brought the first rash of problems with gearbox oil coolers.

Solder holding the coolers together was being melted by the repositioned exhaust with disastrous effect on the gearboxes.

Two of the three cars had to have their gearboxes changed during the race and, at one point, all the R390s were lined up in the pits having the offending units attended to.

During the 13th hour, the Brundle / Muller / Taylor and van de Poele / Suzuki / Patrese entries were withdrawn from the race so there would be enough parts for the best-placed Hoshino / Comas / Kageyama car to finish.

This R390 eventually placed twelfth overall and fifth in the GT1 class, but progress was hampered by two separate gearbox rebuilds.

Given TWR’s previous success at Le Mans, the 1997 R390 programme was an undeniable disappointment.

Ironically though, TWR’s credentials were enhanced as their Porsche WSC-95 won outright for the second year in succession.

An uprated R390 would be back for 1998.

Text copyright: Supercar Nostalgia

Photo copyright: Nissan - https://www.nissan-global.com