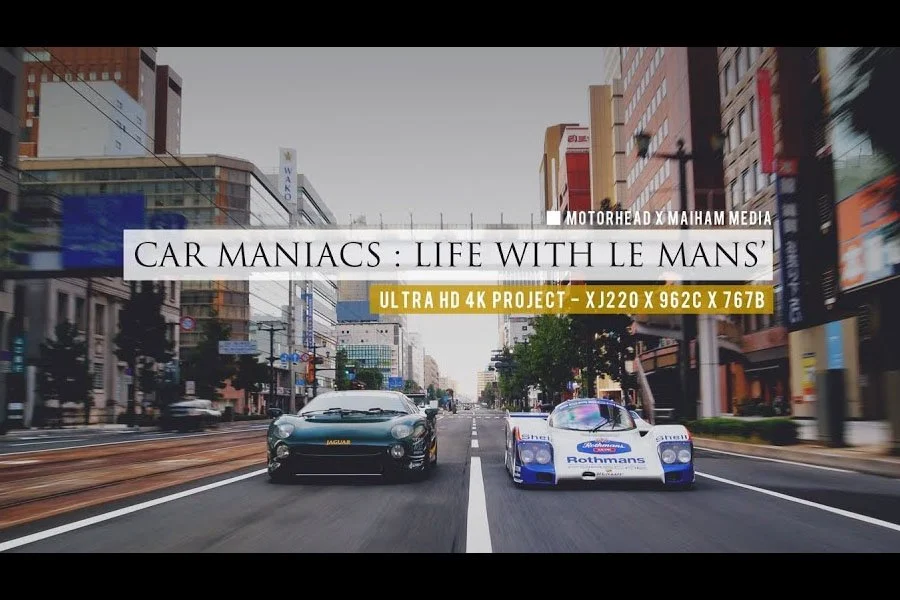

Video: Car Maniacs - Life with Le Mans by Motorhead

/Motorhead magazine teams up with Luke Huxham to give you a glimpse into the life of three young, at-heart car enthusiasts who own three extremely unique Le Mans cars: the Mazda 767B, a Jaguar XJ220LM, and the already famous road-going Porsche 962C.

Read More