Guide: X Factor - a Historical & Technical Appraisal of the Ferrari 512 BB LM

/BACKGROUND

Within a few years of the deal that had seen Fiat acquire a 50% stake in Automobili Ferrari, the Cavallino Rampante had disappeared from Sports and GT racing.

This decision to quit coincided with an Oil Crisis that struck during the winter of 1973-1974 when war in the Middle East broke out, gas prices rose exponentially and demand for high performance vehicles dropped off a cliff.

To streamline its competitive endeavours and cease any inter-group rivalry, Fiat decided Formula 1 would become Ferrari’s domain. Once the radical mid-engined Stratos had fulfilled its potential on the special stages, Sports and GT racing would ultimately be where the Lancia brand was promoted. Rallying would be left to Fiat.

Having tentatively experimented with racing iterations of the Stratos, Lancia finally got its act together for the 1979 season when a Group 5 version of the Montecarlo Turbo came on stream. However, by this time, some of Ferrari’s customers had already convinced the firm to create (and bankrolled development of) a lightly modified 512 BB for the 1978 Le Mans 24 Hours.

With no funding issues and a lack of any direct conflict with other Fiat Group subsidiaries, the resultant 512 BB Competizione had been given the green light.

Despite the fact that none of the 512 BBs that ran at Le Mans in 1978 finished the race (and nor was their much prospect of a class win against a field of heavily modified turbo Porsches), the same clients wanted to go again, but this time with a more radical creation.

As development costs were not an issue, and because said machine would not step on the toes of Lancia’s forthcoming Group 5 Montecarlo Turbo, development of a newly christened Ferrari 512 BB LM was approved.

The BB LM was created to run in the same GTX class as its predecessor. This was a category for Grand Touring Experimental vehicles similar to Group 5 machinery, but for which the normal homologation requirements of 400 base cars within a 24 month period did not apply.

Ferrari developed the 512 BB LM for use at ultra high speed tracks such as Le Mans and Daytona where media interest was highest and the car would be less disadvantaged by its lack of a turbocharged engine.

The first batch of 512 BB LMs was constructed over the winter of 1978-1979. Each chassis was pulled from the production line and sent to Ferrari’s Assistenza Clienti department in Modena where a meticulous assembly process took place.

News of the model broke in January 1979 when Claude Ballot-Lena and Michel Leclere were spotted conducting a twelve hour test at Fiorano. The 512 BB LM subsequently made its competition debut at the Daytona 24 Hours which took place over the weekend of February 3rd and 4th where a trio of cars were entered by Ferrari’s French and US distributor teams (Pozzi and NART).

Ferrari went on to announce a production run of 25 units.

CHASSIS

The transition to LM trim saw each BB-type tubular steel semi monocoque chassis modified to reduce weight and increase rigidity.

Specially honed subframes at either end carried the suspension and combined engine / transmission unit. All told, an extraordinary 90kg was cut from the chassis alone.

As per the stock BB, suspension was independent all round with unequal length wishbones, coil springs, telescopic shocks and anti-roll bars. Twin spring / shock assemblies were once again used per side at the rear. For the LM, the shocks were replaced with adjustable Koni units and rubber bushes made way for uniball joints. Anti-roll bars also became adjustable.

To further reduce weight, the brake system (which used ventilated discs all round) was stripped of its servo assistance.

15-inch diameter centre lock Campagnolo wheels were widened from 7.5 to 10-inches up front and from 9 to 13-inches at the back. Track expanded by 63mm at the front axle and 50mm at the rear.

Twin fuel tanks with a combined 120-litres were once again mounted either side of the engine, up against the rear bulkhead. However, these were now competition-grade units with quick filler caps sunk into the rear fenders.

ENGINE / TRANSMISSION

Compared to the original 4.4-litre Flat 12 all-alloy engines in the 365 GT4 BB, 512 BB motors had been stretched to five-litres by expanding the cylinder bores by 1mm (to 82mm) and extending the stroke by 7mm (to 78mm). The standard car’s 4942cc displacement was carried over for the LM.

Other changes ushered in for the 512 BB road car had included dry-sump lubrication and increased compression.

For the BB LM, an array of hot parts were added by the Customer Assistance department.

The long list of enhancements included lightweight cylinder heads, high lift camshafts, lightened and polished connecting rods, bigger inlet and exhaust ports, optimised valve timing and a free flow competition exhaust. The cooling system was also comprehensively uprated.

The bank of four Weber 40 IF3C downdraught carburettors normally used were replaced with a mechanical (and later electronic) Lucas indirect fuel-injection system. Ignition was via an electronic single plug arrangement.

With compression hiked from 9.2:1 to 10.3:1, Ferrari initially quoted a power output of 460bhp at 7250rpm (compared to 360bhp at 6800rpm for the road version).

As transmissions had been the weak point for those cars that ran at Le Mans in 1978, Ferrari added a lightened and strengthened five-speed gearbox compete with separate oil cooler. A twin-plate clutch and ZF limited-slip differential were also fitted.

BODYWORK

The GTX class in which the BB LM would compete was broadly similar to the FIA’s Group 5 ruleset which permitted dramatic changes to the homologated base car outboard of the bulkheads.

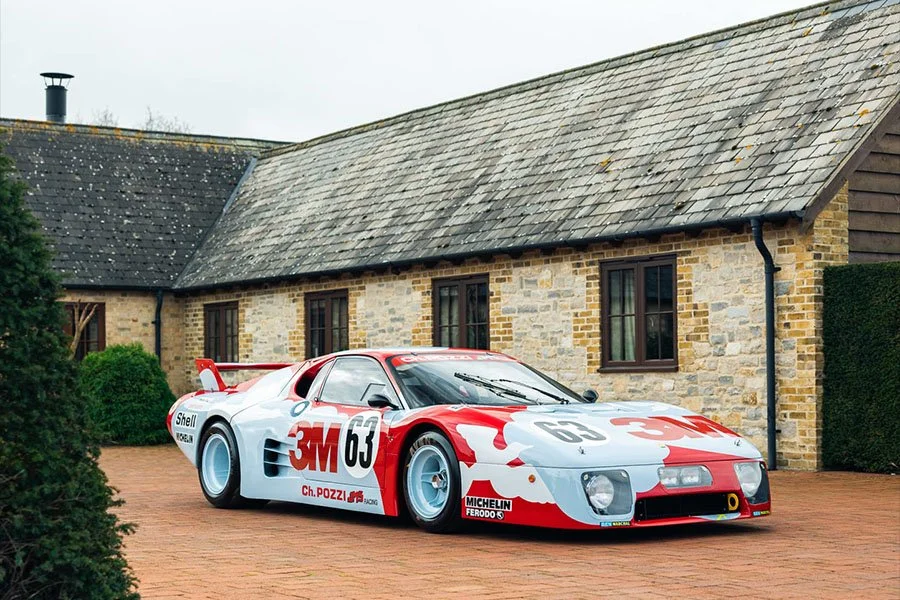

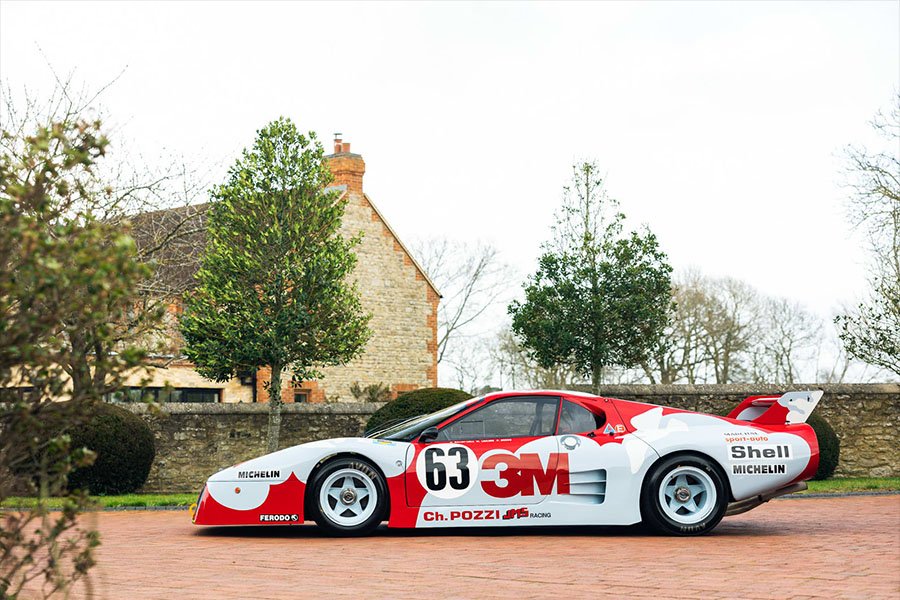

Ferrari commissioned Pininfarina to develop a new super lightweight body for the LM and what emerged was a wind tunnel-honed design that shared little in common with the standard BB other than for its roofline and doors. These much longer and wider low drag bodies were fashioned from lightweight composite materials over at Carrozzeria Auto Sport run by Franco Bacchelli and Roberto Villa in Bastiglia (a short drive north east of Modena).

No doubt inspired by Porsche’s wild 935/78 that had been dubbed Moby Dick on account of its dramatic body styling, Pininfarina took a similar route with the BB LM.

Like the 935/78, custom front and rear sections featured massive overhangs that added nearly half a metre of length and yielded major stability gains.

Instead of retractable headlights, the nose was characterised by lights mounted behind contoured Plexiglas covers along the jutting front apron. A wide intake fed fresh air to the oil cooler and exited via two large vents positioned above the front axle.

Down each flank, deep side skirts were neatly integrated with the flared fenders necessary to cover the wider wheels. Carved out ahead of the rear wheels was an enlarged version of the standard 512 BB’s NACA cooling duct for the rear brakes. Behind the rear quarter window, Pininfarina added a stepped sail panel that housed a discrete engine cooling intake.

To smooth airflow over the body, the LM featured a sloping rear screen that lay flush with the body whereas the road version had used a small vertical screen with exposed flying buttress-type sail panel arrangement.

At the back, downforce was equalised by a massive adjustable aluminium spoiler. The dramatic back end was also home to an oval tail fascia with BB-style lights mounted on drilled endplates. Inboard of these was a huge rectangular meshed grilled that enabled hot air to escape.

INTERIOR

Inside, the cockpit was stripped of any superfluous equipment and kitted out with all the essential safety gear.

A simplified dash trimmed in anti-glare material replaced the boxy original unit and clustered five gauges behind a small diameter three-spoke Momo steering wheel. Directly ahead of the driver was the BB’s familiar 10,000rpm rev counter. Off to the left were small gearbox oil temperature and water temperature gauges. Another brace of small dials (a combined engine oil pressure / fuel pressure read out and engine oil temperature gauge) were housed to the right of the tacho.

The well-padded seats from the standard 512 BB made way for a single bucket-type unit on the left-hand side only. No door panel trim was fitted; in the door cavity was just a basic pull chord. Fixed Plexiglas side windows had a sliding sub element that could be pulled back to allow fresh air into the cockpit. Additional ventilation came by way of two large pipes exiting from underneath the dash.

To the driver’s right was an open-gate gear lever and a basic control panel that housed the switchgear and an exposed fuseboard.

WEIGHT / PERFORMANCE

At 1110kg, the Customer Assistance department managed to shed an impressive 290kg from the standard 512 BB for these earliest LM variants. By the time the last cars emerged in 1982, this figure had been further reduced with the lightest coming out at 1058kg.

In Le Mans trim, speeds comfortably over 200mph were possible down the Mulsanne Straight (204mph in 1979).

0-62mph times would have been highly dependent on gearbox and rear axle ratios but, with the shortest possible configuration, a time under 4 seconds would have been possible.

PRODUCTION CHANGES

In addition to the aforementioned switch to electronic fuel-injection, the BB LM underwent a number of specification changes during its lifetime.

Ferrari’s second batch of cars (the first of which were completed during May and June of 1980) featured different suspension pick up points, bigger brakes, wider wheels, deeper side skirts, revised rear fender intakes and 500bhp engines.

By the time last handful of cars emerged (of the type destined for Le Mans in 1982), the engine had been moved forward and lower in the chassis and weight had been further reduced.

END OF PRODUCTION

Production ran from January 1979 when the first prototype emerged until November 1982 when the final car was completed.

25 units were built with chassis numbers ranging from 22681 to 44023.

Engines were numbered 0001 to 0032.

COMPETITION HISTORY

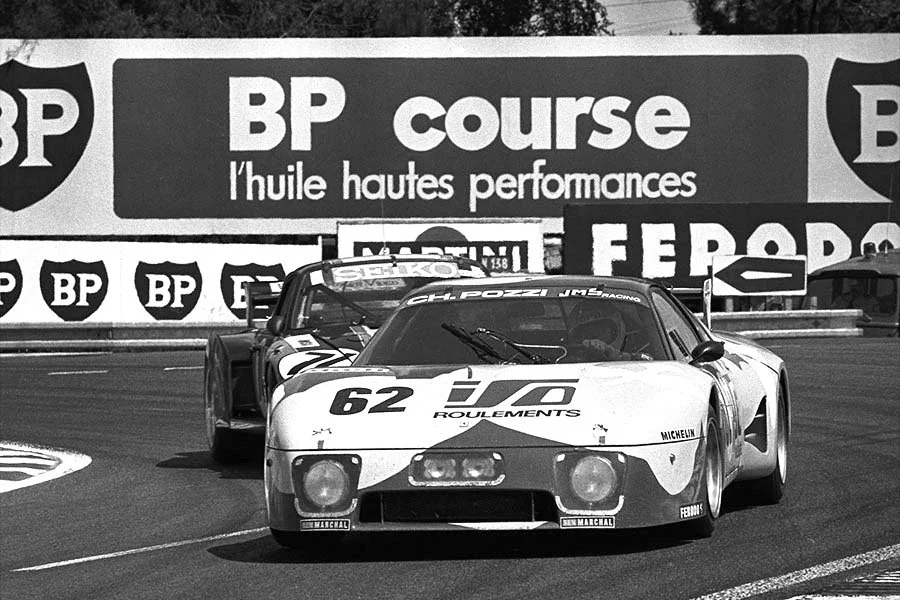

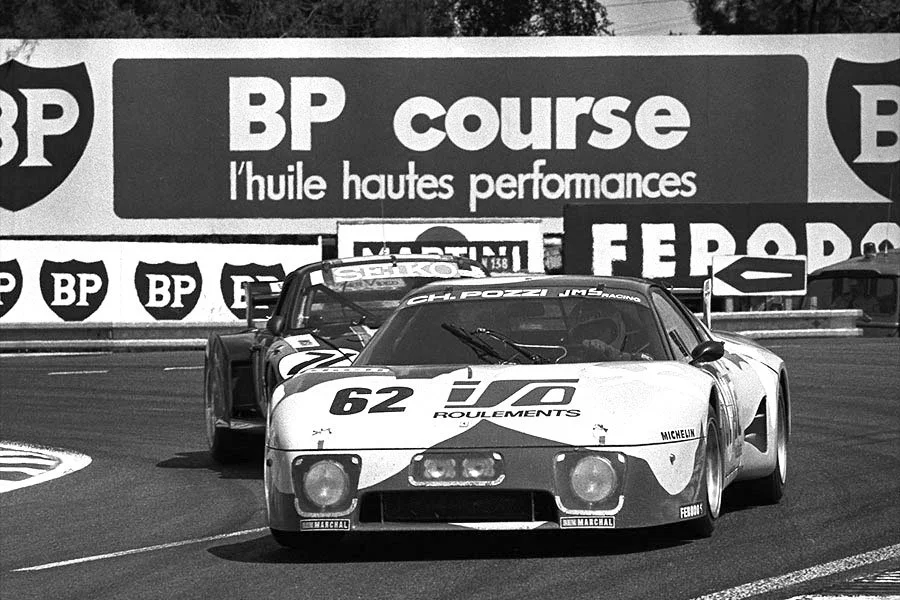

Three BB LMs were on hand for the model’s competition debut at the 1979 Daytona 24 Hours: two from Charles Pozzi and one from NART. Unfortunately, having completed limited high speed testing, they were found to be unstable on the Daytona banking and one of the cars crashed after a tyre blow out in practice. Following another blowout in the race, the remaining pair were withdrawn.

At Le Mans, the same three cars from Daytona were joined by an Ecurie Francorchamps entry owned by Jean Blaton. Ultimately, it was only this new bright yellow machine that finished (twelfth overall, fifth in class) while the others were ruled out by a combination of accidents and engine failure.

More copies of the BB LM arrived on stream for 1980. Single car privateer entries ran at Daytona (Preston Henn), the Monza 1000km (Fabrizio Violati – Scuderia Supercar Bellancauto) and the Riverside 5 Hours (Joe Crevier) but none went the distance. It wasn’t until the Silverstone 6 Hours that a BB LM saw the chequered flag when Steve O’Rourke’s ex-Francorchamps machine placed seventh overall (second in class).

Six BB LMs then appeared at Le Mans. Best placed was the Pozzi entry that finished tenth overall (third in class). The only additional BB LM classified at la Sarthe was O’Rourke’s car which had a drama-filled run to 23rd overall (eighth in class). The other three Ferraris that started (two from Pozzi and the Violati machine) retired owing to either accidents or mechanical issues. Preston Henn’s example failed to start after suffering an engine failure in practice.

Aside from the ex-Francorchamps / O’Rourke machine now run by Modena Engineering (which failed to finish the Silverstone 6 Hours during its only appearance in 1981), the following season was exclusively contested by half a dozen brand new BB LMs.

1981 saw Ron Spangler’s car (run under the Prancing Horse Farms banner) crash out after showing much promise at Daytona (where it was the only BB LM on hand). At the Mugello 6 Hours, Giovanni Del Buono’s new mount placed ninth overall and won its class (although it was the only GTX runner).

The Monza 1000km marked the debut of Fabrizio Violati’s new BB LM which had been built with a special body. It was plagued by overheating issues, but nevertheless finished 15th overall (first in class). The Silverstone 6 Hours then saw Simon Phillips give his recently delivered white BB LM its inaugural run. Differential issues unfortunately meant it dropped out before the end.

Five BB LMs appeared at Le Mans in 1981 where best placed was the single Pozzi entry which finished a superb fifth overall to win its class. Bob Donner’s new car came home ninth overall and third in class for what was the BB LM’s most impressive showing thus far. None of the remaining trio (entered by Violati, Phillips and NART) made it to the chequered flag.

After Le Mans, Fabrizio Violati ran his special bodied example at the Pergusa 6 Hours and finished fifth overall (first in class). The BB LM’s final appearance of 1981 came at the Birkett 4 Hour Relay around Silverstone where Simon Phillips’ car had a massive accident that necessitated a full rebuild using a new chassis.

1982 was the last year that the BB LM ran as a current model. Two new cars appeared that season while seven existing chassis also raced.

Daytona was another wash out, as was the model’s first appearance at the Sebring 12 Hours with no finishers at either event. The special bodied Violati machine then placed eighth overall to win the GTX class at the Monza 1000km and Simon Phillips’ rebuilt BB LM placed 17th overall at the Silverstone 6 Hours (second in class).

Four cars were then in attendance at Le Mans where Ron Spangler’s machine bagged sixth overall (third in class) and the NART entry finished ninth (fourth in class). Neither the Pozzi or Preston Henn Ferraris made the finish.

The last two events of 1982 saw Violati’s special bodied BB LM place tenth overall (first in class) at the Mugello 1000km, after which Preston Henn appeared with his car at the Fuji 6 Hours where it crashed out.

BB LMs continued to race in private hands until 1985, albeit without much success.

Text copyright: Supercar Nostalgia

Photo copyright: unattributed & Girardo & Co. - https://girardo.com/