Guide: Ferrari 250 LM - a Historical & Technical Appraisal

/BACKGROUND

Beginning in 1962, the governing body of motor sport decided the de facto World Sports Car Championship would be decided by cars from the Grand Touring category.

By contrast, purpose-built Sports Prototypes would be limited to a comparative handful of blue ribband events on the calendar, the points from which would go towards a separate contest.

As a result, manufacturers began to take the GT class ever more seriously, not least Ferrari who created the rule-bending 250 GTO for that ‘62 campaign.

At the time, the Group 3 GT class stipulated that 100 production vehicles had to be built within a twelve month period to qualify. Special coachwork was permitted for racing variants of the homologated model, but the mechanicals could not be modified. The FIA also permitted chassis strengthening, but not chassis weight reduction.

As the 250 GTO had used a custom small diameter tubular frame unlike any other 250 GT, it should have been thrown out unless 100 had been built.

However, such was Enzo Ferrari’s influence that the FIA allowed the GTO to race.

Unsurprisingly, it went on to dominate in both 1962 and 1963.

No doubt emboldened by his ability to get away with such a flagrant breach of the sporting code, Enzo Ferrari made an even more ambitious play for the 1964 season when he tried to get the mid-engined 250 LM approved as a Group 3 GT car following its debut at the Paris Motor Show in October 1963.

Created in response to a special-bodied Shelby Cobra that Ford were known to be bankrolling for 1964 (the Shelby Cobra Daytona), the switch to a mid-engined layout without a 100-car production run having been completed was a step too far even for the FIA which had mockingly been dubbed Ferrari International Assistance in response to their earlier capitulation.

Accordingly, Ferrari’s application was rejected which left the 250 LM to play out most of its career in the Prototype class.

Once it became clear the governing body were not going to budge on their decision, Ferrari was forced to rush through the development of an updated second series 250 GTO with low drag bodywork.

As for the 250 LM, with a 3-litre ‘250’ engine no longer a requirement, Ferrari installed every car with a 3.3-litre ‘275’ engine but retained the original ‘250’ moniker for marketing reasons.

CHASSIS

Despite a strong visual link with the 250 P raced so successfully throughout 1963, the 250 LM was quite different under the skin.

Both cars featured a welded tubular steel chassis, but where the 250 P derived much of its strength from stressed alloy panels riveted over the tubes for a semi-monocoque effect, the 250 LM used diagonally trussed tubes, especially around the cockpit, lower sills and doors.

Designated Tipo 577, the 250 LM chassis retained a 2400mm wheelbase as per the 250 GT SWB and GTO, but that was where any similarity ended.

Suspension was independent all round with unequal length wishbones, coil springs and telescopic Koni shocks. An anti-roll bar was fitted at either end.

Dunlop disc brakes with a 303mm diameter were used up front while those at the rear measured 308mm.

The 15-inch diameter Borrani wire wheels were initially 5.5 and 7-inches wide front to rear respectively.

Overall fuel capacity was 130-litres with a brace of 65-litre fuel cells located between the rear bulkhead and wheels on both sides of the car.

ENGINE / TRANSMISSION

The 250 LM prototype (chassis 5149 GT) initially appeared with a Tipo 128 LM three-litre 60° V12 that displaced 2953cc thanks to a bore and stroke of 73mm and 58.8mm respectively.

The Tipo 128 LM motor was an all-alloy dry-sumped power unit with single overhead cam Testa Rossa-derived cylinder heads, high-lift camshafts, high compression pistons and special connecting rods. Ignition was via a single spark plug per cylinder and two coils.

With six twin choke downdraught Weber 38 DCN carburettors and a 9.7:1 compression ratio, these engines produced a peak output of 300bhp at 7500rpm and 217lb-ft at 5500rpm.

After the FIA rejected Ferrari’s attempt to get the 250 LM homologated in Group 3 there was no longer a reason to stick with a three-litre ‘250’ motor. With this in mind, Ferrari opted for enlarged 3.3-litre motors bored out by an additional 4mm which took overall capacity to 3286cc (a gain of 333cc).

The Tipo 211 motor was fitted to around two thirds of the production run and used an identical 9.7:1 compression to the original three-litre engine. It produced a peak output of 320bhp at 7500rpm and 231lb-ft at 5500rpm.

The Tipo 210 engine fitted to around a third of the production run was slightly de-tuned with a 9.5:1 compression ratio. It developed a little less power at the top end (310bhp at 7500rpm) but the torque rating was unaffected and engine manners were slightly improved.

Weber 38 DCN and 40 DCN carburettors were variously fitted to these 3.3-litre engines.

Transmission was through a five-speed gearbox with single-plate clutch and ZF limited slip differential.

BODYWORK

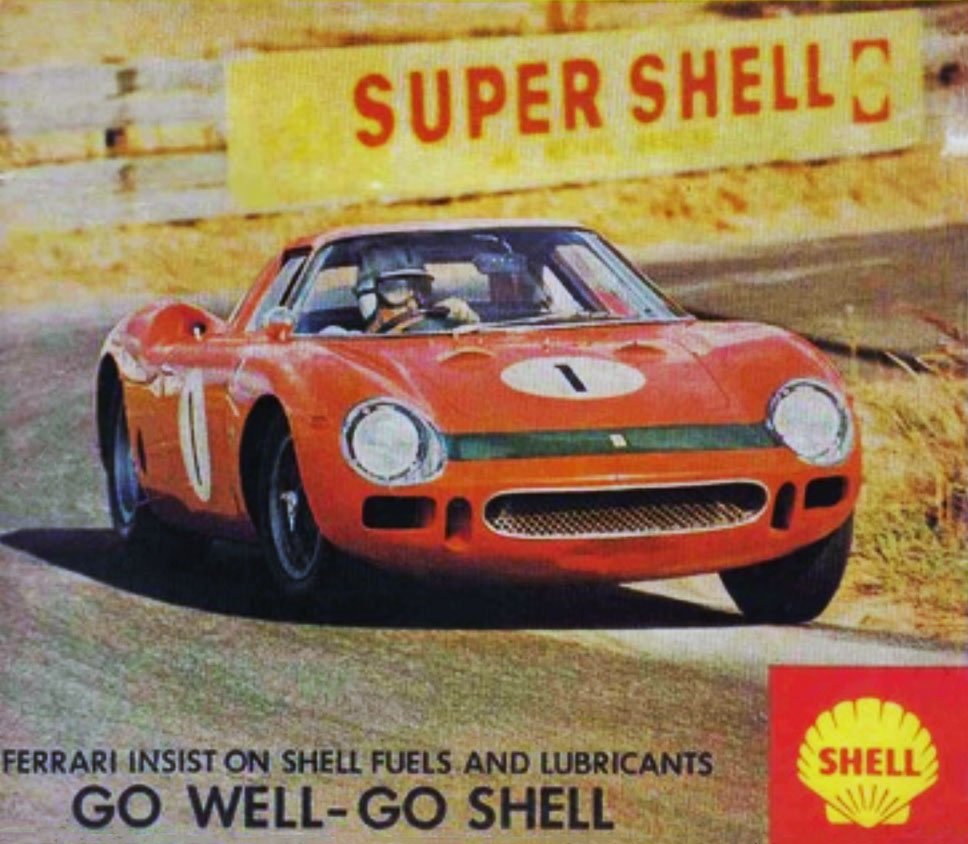

The 250 LM’s bodywork was designed by Pininfarina who applied many of the lessons learnt from Ferrari’s P-car programme.

Unlike the 250 P of 1963 and the subsequent 275 P / 330 P of 1964, the 250 LM was built exclusively as a Berlinetta whereas the aforementioned Prototypes ran open cockpits.

Body panels were fashioned from the thinnest available aluminium over at the Scaglietti works in Modena.

Up front, the head and supplementary light assemblies were mounted behind glass covers with natural aluminium bezels. In between, the wide central intake was flanked by vertical brake cooling slots while further up, bulbous fenders stood proud of the flattened central nose section. A pair of Plexiglas cowls fed fresh air into the otherwise stiflingly hot cabin.

The cockpit area itself featured an expansive wraparound windscreen with single wiper, sliding two-piece Plexiglas side windows and a tunnelled roof section that smoothed airflow towards the rear of the car.

Further back, shapely rear fenders were home to shoulder-mounted engine cooling intakes. Lying in between them was a flattened rear deck that culminated with a discrete spoiler. Three huge meshed grilles were cut from the Kamm tail fascia in order for hot air to escape from the engine bay.

Several of these details (the extended roof tunnel, the faired-in supplementary front lights clusters, the cockpit ventilation scoops, single wiper and shoulder-mounted intakes) had not appeared on the original ‘63 Paris Show car but were refined over winter of 1963-1964 and applied to the subsequent production run. The prototype (depicted above) also featured a distinctive roof-mounted aerofoil at the trailing edge of the cockpit which was not seen again.

INTERIOR

Inside, the 250 LM bore practically no resemblance to any Ferrari production car.

Entry required the occupant to scramble over wide side sills and then drop oneself into a fabric-trimmed bucket seat which offered only fore / aft adjustment. In between the two seats was a centrally located gear lever with open gate and reverse gear lockout.

Directly behind the wood-rimmed steering wheel with its trio of highly polished aluminium spokes was a slim binnacle that housed a 10,000rpm rev counter flanked by smaller read outs for oil pressure and water temperature. An oil temperature gauge and two fuel dials were located on the aluminium bulkhead panel outboard of the steering wheel.

Located centrally underneath the crackle black dash was a control panel with an array of toggle switches and warning lights.

Aside from the seats, there was no upholstery to speak of and the door panels were simply an exposed cavity with a pull chord for exiting the vehicle.

WEIGHT / PERFORMANCE

At just 820kg the 250 LM weighed 60kg less than the 250 GTO from which it was supposedly derived.

With the longest ratio Le Mans gearing, top speed went from 174mph to 179mph.

With the shortest gear ratios, 0-62mph was possible in around 4.5 seconds.

250 LM STRADALE CHASSIS 6025 LM

At the Geneva Motor Show in March 1965, Ferrari and Pininfarina tried to drum up some interest for a road-focused 250 LM based on an extended 2600mm wheelbase chassis created to increase cockpit space.

Based on chassis 6025 LM, the white and blue-striped machine receiced a carefully tweaked aluminium body fabricated at the Pininfarina works in Grugliasco as opposed to the Scaglietti facility in Modena (where the production 250 LM shells were produced).

Most notably, the 250 LM Stradale featured an extended nose, chrome and rubber bumperettes at either end, Gullwing-style roof panels that tilted upwards for easy access, re-profiled doors, a Fastback rear windscreen and myriad new cooling solutions.

Inside, Pininfarina fitted proper seats and door panels, electric windows and a new dash. The cockpit was upholstered in a mix of plain and quilted red leatherette with matching carpets all of which offset nicely against the black dash and door caps.

Unfortunately, the 250 LM Stradale did not attract sufficient attention for the dozen-or-so orders needed to justify a short production run and 6025 LM remained a one off.

250 LM STRADALE CONVERSION CHASSIS 5995 LM

During 1967, Ferrari themselves converted a 250 LM to more road-oriented trim on behalf of one of the firm’s best customers, Scuderia Serenissima patron and aristocrat, Count Giovanni Volpi di Misurata.

New equipment fitted to chassis 5995 LM included a set of bumpers, uprated light fairings, electric glass side windows with quarterlights and a single-piece Plexiglass Fastback rear window. To improve cockpit ventilation, triangular ducts were cut away from the front lid.

During this expensive conversion, any bodywork imperfections were rectified and 5995 LM was subsequently re-painted a handsome shade of Argento from its original Rosso Cina.

PRODUCTION RUN

Following the prototype displayed at the Paris Salon in October 1963, an additional 30 250 LM production cars were built along with the unique long wheelbase Stradale.

Of the 30 production cars, most were completed between February and October 1964, after which just a quintet of examples emerged during 1965 followed by the last example (chassis 8165 LM) in May 1966.

The overwhelming majority of cars were painted Rosso Cina (China Red) with Blu fabric seats.

Only three cars (chassis 5891 LM, 5903 LM and 5995 LM) were built in left-hand drive with the rest of the production run in right-hand drive.

One car (chassis 6233 completed in June 1965) wore a fibreglass instead of aluminium body.

COMPETITION HISTORY

Aside from the 1964 Targa Florio (which fell to Porsche), Scuderia Ferrari’s 275 P won all the remaining races which formed that year’s International Prototype Trophy (the Sebring 12 Hours, Nurburgring 1000km and Le Mans 24 Hours). Several of the remaining races on the caldendar allowed Prototypes to compete, but at these events there no points on offer for such machinery.

The most significant result for a 250 LM in the remaining World Championship races was achieved by the Maranello Concessionaires 250 LM of Graham Hill and Jo Bonnier (chassis 5907 LM) that won the Reims 12 Hours outright on July 7th. A NART-entered sister car allocated to factory drivers John Surtees and Lorenzo Bandini (chassis 5909 LM) came home second.

The only other win for the 250 LM at World Championship level in 1964 came at the Sierre Montagna Hillclimb in Switzerland where Scuderia driver Ludovico Scarfiotti scorched up the course to take victory in the Scuderia Filipinetti-owned chassis 5899 LM.

Elsewhere, 1964 also saw Lucien Bianchi win the Zolder Grand Prix for Ecurie Francorchamps (5843 LM), Roy Salvadori win the Scott-Brown Memorial race at Snetterton for Maranello Concessionaires (5907 LM) and Walt Hansgen / Augie Pabst win the Road America 500 for John Mecom Jr. (6047 LM).

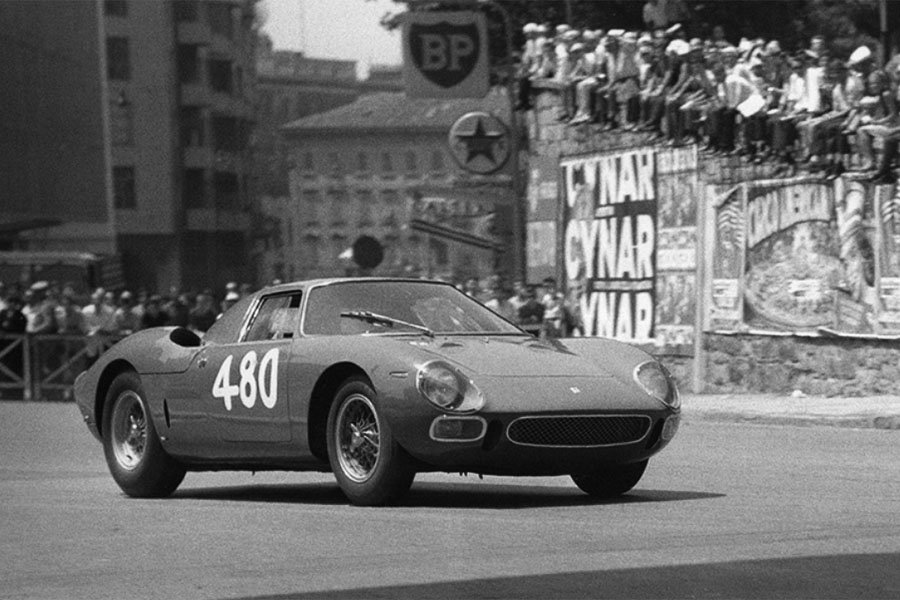

On home soil, Nino Vaccarella won the Monza Coppa Inter-Europa for Scuderia Filipinetti (chassis 5899 LM). Vaccarella finished ahead of second placed Roy Salvadori driving for Maranello Concessionaires (5895 LM) and David Piper who took the final podium spot in his privately owned example (5897 LM).

In the southern hemisphere, David Piper and Tony Maggs won the Kyalami 9 Hours for Maranello Concessionaires in chassis 5907 LM. Four weeks later, Willy Mairesse headed a 250 LM 1-2-3 at the Angolan Grand Prix for Ecurie Francorchamps in chassis 6023 LM. Rounding out the podium were Lucien Bianchi (5843 LM, Equipe National Belge) and Herbert Muller (6119 LM, Scuderia Filipinetti).

For 1965, the FIA expanded the number of points-scoring World Championship events open to Prototype machinery. As expected, Scuderia Ferrari’s new P2 racer was the car to beat and won the Monza 1000km, Targa Florio, Nurburgring 1000km and Reims 12 Hours.

However, when the P2s fell by the wayside at Le Mans, it was a NART 250 LM that emerged victorious thanks to Jochen Rindt, Masten Gregory and Ed Hugus. Their car (chassis 5893 LM) was running the new-for-1965 Drogo long nose, an upgrade subsequently retro-fitted to quite a few 250 LMs.

Elsewhere in the world series, Willy Mairesse won the Spa 500km (6023 LM, Ecurie Francorchamps) and Mario Casoni / Antonio Nicodemi headed a 250 LM 1-2-3 at the Mugello Grand Prix driving Nicodemi’s privately owned example (chassis 5891 LM). Second spot went to Maurizio Grana / Cesare Topetti (5995 LM, Count Giovanni Volpi) and Oddone Sigala / Luigi Taramazzo placed third (6173 LM, Scuderia St. Ambroeus).

Mario Casoni also won the Coppa Citta di Enna World Championship race driving Antonio Nicodemi’s car (5891 LM) and David Piper claimed second in his privateer example (5897 LM).

Outside of the 1965 World Championship, Le Mans-winner Jochen Rindt secured victory in the Zeltweg 200 mile race in Gotfried Koechert’s 250 LM (chassis 5845 LM).

1965 was a successful season for Italian privateer Edoardo Lualdi-Gabardi who won eight mountain climbs in his 250 LM to emerge as the 1965 domestic hillclimb hampion. Lualdi-Gabardi’s outright victories comprised the Coppa Gallenga Vermicino-Rocca di Papa, Stallavena-Boscochiesanuova, Cividale-Castelmonte, Coppa Citta di Volterra, Vezzano-Casina Reggio Emilia, Predappio-Rocca delle Caminate, Trieste-Opicina and Agordo-Frassene hillclimbs.

Over in Australia, Spencer Martin won eight races in a 250 LM on his way to becoming that year’s Gold Star champion. Driving the Scuderia Veloce example owned by David McKay (6321 LM). Martin won the Perth 6 Hours, two races at Warwick Farm, another two at Longford and one apiece at Sandown Park, Lakeside and Catalina Park.

Back in Europe, Ecurie Francorchamps won the Coupes des Belges thanks to Willy Mairesse (6023 LM).

A host of minor events were also won by 250 LM drivers in what turned out to be the car’s best year of competition.

For 1966, new regulations were brought in which split Prototypes and Sports cars into separate categories with a zero and 50 car production requirement for each respective class. Grand Touring machinery now had to meet a 500 car target instead of just 100 units.

Although the 250 LM was permitted to race in the Group 4 Sports car class despite not having reached the 50 car homologation requirement, it was generally no match for the newer Ford GT40 Mk1. By this time, many cars had been uprated to wider wheels (6.5 or 7-inches at the front and 8 or 8.5-inches at the rear).

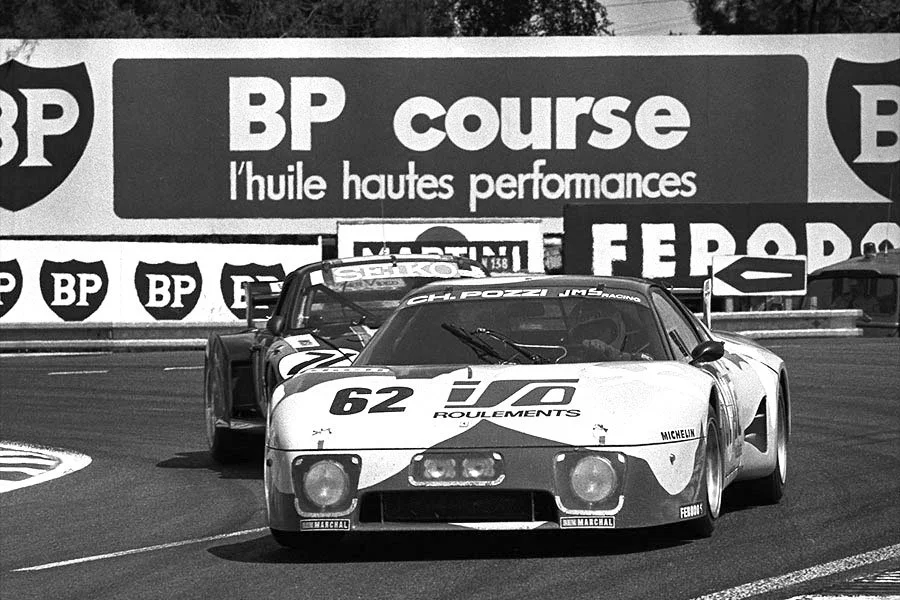

Despite having owned a 365 P2 as well, David Piper was arguably the most successful 250 LM driver of 1966. With his brace of cars he picked up wins at the Brands Hatch Eagle Trophy (5897 LM) and the Crystal Palace Anerley Trophy, Oulton Park Gold Cup and Paris 1000km at Montlhery (all in 8165 LM, the latter co-driving with Piers Courage).

Perhaps an even more significant win for the 250 LM in 1966 came at the Surfers Paradise 12 Hours where Jackie Stewart and Andy Buchanan claimed top spot for the Scuderia Veloce example owned by David McKay (6321 LM).

Elsewhere, Edoardo Lualdi-Gabardi picked up a trio of wins in 6217 LM at the Coppa della Collina Pistoiese, Coppa Citta di Volterra and Coppa Acqua Cerelia.

Also on Italian soil, Antonio Nicodemi and Giorgio Pianta won the Rallye Jolly Hotels in Nicodemi’s personal car (5891 LM).

The 250 LM continued to be a potential race winner in the right hands up until the end of 1967 and some cars were still running as late as 1970.

Text copyright: Supercar Nostalgia

Photo copyright: Ferrari - https://www.ferrari.com & RM Sotheby’s - https://rmsothebys.com/