Guide: Porsche Goes All In - a Historical & Technical Appraisal of the Porsche 917

/BACKGROUND

One day after the 1967 Le Mans 24 Hours had seen all previous records broken, the FIA announced a three-litre engine limit would be imposed on top flight Group 6 Prototypes from 1968. The drastic move was an attempt to reduce speeds with 1967’s race-winning Ford GT Mk4 having hit in excess of 230mph down the Mulsanne Straight.

Whereas the Group 6 Protoype class (which had no minimum production requirement) would be forced to run engines no bigger than three-litres in 1968, the existing Group 4 Sports car class would remain in its existing guise: 50 cars needed for homologation with engines of up to five-litres permitted.

As he considered the unilateral move to three-litre engines for Group 6 to blatantly favour Porsche, an incensed Enzo Ferrari did not enter the 1968 World Sportscar Championship and elected to go Can-Am racing instead. Ford also quit, which left the series without arguably its two biggest names.

The opening races of 1968 saw three-litre Group 6 cars from Porsche (907 / 908) and Alfa Romeo (T33/2) go head-to-head. Machinery from Alpine (A220) and Ford UK (P68 F3/L) came on stream at select rounds a little later.

Meanwhile, the Group 4 Sports class was even more poorly attended with the odd privateer Lola T70 GT pitched up against some ageing Ferrari 250 LMs and John Wyer’s Gulf-backed Ford GT40s (Wyer had acquired Ford Advanced Vehicles along with GT40 production rights on Ford’s 1967 exit).

Realising early on that crowds and sponsors wanted to see more big-engined cars, in April 1968 the FIA decided to try and stimulate entries into the Group 4 category with its up to five-litre engine rule. Their approach was simple: they announced the 50-car homologation requirement would be slashed to just 25 units for 1969.

Over in Stuttgart, several weeks of deliberation followed with regard to which class should be pursued. On the one hand, Porsche’s under three-litre 907 / 908 had the pace to win on handling circuits. However, thanks to its effectiveness on power tracks, the five-litre Gulf GT40 (which despite all the latest bells and whistles was still a four-year old design) was expected to provide seriously stiff opposition for overall 1968 championship honours.

In July 1968, the decision was made: despite having only just finished the new 908 Group 6 car, Porsche would begin development of a brand new five-litre Flat 12-engined machine for the Group 4 Sports category.

The twist was, the resultant 917 was in reality a purpose-built Prototype and, by meeting the 25 car Group 4 production rule, the FIA would have no choice but to rubber stamp Porsche’s application. This would enable the German firm to run five-litre engines in a purebred Prototype and thus get a massive advantage over the rest of the field.

To offset some of the enormous expense involved in developing and building such a quantity of cars, the 917 would be available to anyone with enough money to buy one.

Owing to its rule-bending nature, the 917 programme was conducted in great secrecy. No mention was even made at Porsche’s Hockenheim press day in January 1969. Instead, it came as a complete surprise when the 917 was unveiled at the Geneva Motor Show on March 12th 1969. A price of DM 140,000 was quoted which equated to £14,500 or $35,000 at period exchange rates.

Porsche applied for homologation on 20th March 1969 when the FIA inspectors were shown half a dozen completed cars plus parts for the rest. However, the governing body wanted to see 25 finished cars and, as the racing team was already flat out, Porsche were forced to draft in all kinds of administrative staff to help with assembly.

Three weeks later (on April 20th 1969), 25 fully assembled 917s were displayed in front of the Porsche factory for inspection. Unbeknown to the FIA, many of these ‘secretary-built’ cars could have their engines started and first gear engaged, but could drive no more than a few metres. The 917s were lined up in such a way that most could be manoeuvred forwards but not actually driven out.

Homologation was granted and became effective from May 1st.

The majority of cars were then dismantled to be properly re-assembled at a later date as and when required.

CHASSIS

The 917 was assembled around a complex, super lightweight aluminium-tubed spaceframe that combined elements of the 908 and 909 Bergspyder. Despite having been suitably reinforced to handle the prodigious engine output forecast, it weighed just 42kg.

The chassis was constructed of a new aluminium alloy that took almost a year to perfect welding techniques on. The tubular framework was also used to pipe oil to the front radiator. It was permanently gas-pressurised to detect any cracks in the welded structure.

In typical Porsche fashion, the 917 used a relatively short wheelbase of 2300mm.

Independent coil sprung double wishbone suspension was fully adjustable. Bilstein dampers were installed along with front anti-dive geometry.

Exotic alloys were used extensively: the hubs, springs, gear lever and steering column were titanium while the wheels and uprights were magnesium.

Ventilated disc brakes and ATE calipers were fitted at each corner along with centre-lock five spoke wheels originally shod with custom Dunlop tyres. Of 15-inch diameter, the wheels initially measured 9-inches wide at the front and 12-inches wide at the rear.

A 60-litre fuel tank was housed in each sill.

ENGINE / TRANSMISSION

For the 917, Hans Mezger created Porsche’s first twelve cylinder engine: an air-cooled 4.5-litre 180° Flat 12 given type number 912/00.

Effectively a combination of two Porsche 2.25-litre Flat 6 engines, the 912/00 motor featured a crankshaft divided in the middle that rested on plain bearings with titanium connecting rods. At the centre of the engine, a train of gears drove four camshafts operating two valves per cylinder and the vertical shaft for a large horizontally-mounted air-cooling fan.

Mezger’s engine comprised a magnesium alloy block and light alloy head. It displaced 4494cc thanks to a bore and stroke of 85mm and 66mm respectively.

The reason Porsche did not go for a full five-litre motor at this stage was two-fold: they didn’t think the extra capacity would be necessary to win and, to save time, things like the bore, stroke, valve and port sizes of the 908 had simply been carried over.

Mechanical Bosch fuel-injection was employed and there were two separate ignition distributors feeding the 24 spark plugs.

With compression set at 10.5:1, the new engine initially produced a peak output of 520bhp at 8000rpm and 333lb-ft at 6500rpm.

The longitudinally mounted all-synchromesh gearbox was designed to take four or five gears. Transmission was through a triple-plate clutch and limited-slip differential.

BODYWORK

Like most of Porsche’s purpose-built racing cars from this era, the 917 looked handsome and clinical.

A natural evolution of the 907 / 908 theme that had been continually refined throughout 1968, the 917 came with a cutting edge aero kit that comprised canards at each front corner and moveable tail flaps that reacted to the suspension and either created lift or downforce according to what was required.

As per the regulations, a full complement of road equipment (proper lighting and a spare wheel / tyre) was carefully integrated to the design.

Aside from detachable panels like front lid, doors and the engine cover, most of the 917’s fibreglass body panels were glued to the tubular frame.

Two interchangeable fully enclosed lift-up rear body sections were developed for circuits with high and low speed characteristics (long and short respectively).

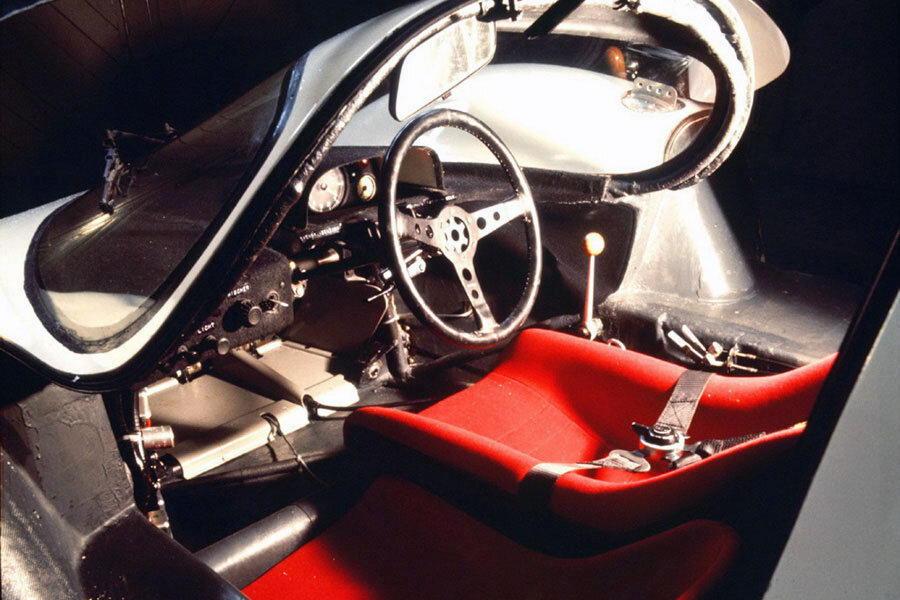

INTERIOR

In compliance with the rulebook, the 917’s cockpit was notionally suitable for two occupants on account of a tiny seat (untrimmed and uninviting) mounted in the left-hand side of the cockpit.

The cabin was necessarily positioned well forward in the chassis to accommodate Porsche’s huge new Flat 12 engine. Additionally, the driver was forced to sit at an almost 45° angle with his feet hung out over the front axle.

Aside from a little padding on the driver’s seat, there was no upholstery, no sound deadening and no creature comforts.

One nice touch was a traditional birch wood gear knob.

The main instruments were displayed in a simple crackle black dash.

All 917s were right-hand drive with a right-hand gearchange.

WEIGHT / PERFORMANCE

The completed car weighed in at 895kg. The class minimum was 800kg.

0-62mph required less than three seconds and the long tailed version had a top speed in the region of 220mph.

PRODUCTION

Of the 25 ‘completed’ 917s lined up outside the factory for the FIA inspection in April 1969, only ten (chassis 001 to 010) went on to see some kind of use in 1970 (either as a show, test or race car).

In addition to subtle aerodynamic refinements, Porsche uprated the 917 during the course of the 1969 season with a more powerful 585bhp engine (from Le Mans) and wider wheels / enhanced brakes (at Zeltweg).

COMPETITION HISTORY

As a consequence of Porsche’s determination to take championship honours in 1969, the at this stage ill-handling 917 generally played second fiddle to Porsche’s bona fide three-litre Group 6 car, the 908.

Following its debut at the Le Mans Test weekend in late March (where Rolf Stommelen went three seconds faster than anyone else), Porsche campaigned the 917 at Spa, the Nurburgring, Le Mans and Zeltweg.

Having set a time good enough for pole at Spa in a 917, Porsche’s number one driver pairing of Jo Siffert / Brian Redman elected to use a 908 in the race. Hans Herrmann and Uwe Schutz qualified their 917 in eighth, but the car’s engine didn’t even last a lap.

Experienced pro’s Frank Gardner and David Piper were brought in to drive the 917 at Nurburgring (finishing eighth) after which two cars appeared at Le Mans. Now in long tailed trim, there were three 917s on hand: the works cars of Rolf Stommelen / Kurt Ahrens Jr. and Vic Elford / Richard Attwood (which started first and second but failed to finish) along with a privateer entry that Porsche had brought along for John Woolfe who was unfortunately involved in a horrible fiery opening lap fatal crash.

In Austria four weeks later, the 917 finally came good when Siffert and Ahrens Jr. won the Zeltweg 1000km. Team-mates Attwood and Redman were third.

The car driven to third place at Zeltweg was sold to David Piper who used it for three end-of-season events outside of the World Sportscar Championship. He placed sixth overall alongside Jo Siffert in the Japanese Grand Prix at Fuji, drove single-handedly to third in the Hockenheim 300 mile race and then won the Kyalami 9 Hours co-driven by Richard Attwood.

SUBSEQUENT HISTORY

Porsche’s racing department overspent massively during 1969 to the extent that a partner organisation had to be sought to race the 917 in 1970 which would enable factory staff to focus fully on development: Porsche had spent DM 30 million (£3.1m / $7.5m) on the combined 908 and 917 projects in one year alone.

The company turned to John Wyer Automotive Engineering (JWAE) whose Gulf Oil-backed operation were the undisputed masters of endurance racing. Wyer would get the cars at no cost but, from the moment everything left Stuttgart, it was at JWAE’s expense. The partnership was announced in London during October 1969.

However, head of the compeitition department (and grandson of Ferdinand Porsche), Ferdinand Piech, still wanted to race the 917 in 1970. Accordingly, quasi works examples were also campaigned under the Porsche Konstruktionen Salzburg banner (Piech’s mother’s Austrian Porsche distributor).

Two new stand-alone versions of the 917 would be developed for the 1970 and ‘71 seasons: the 917 K and 917 L.

Text copyright: Supercar Nostalgia

Photo copyright: Porsche - https://www.porsche.com & unattributed