Guide: The New Standard - a Historical & Technical Appraisal of the McLaren F1

/BACKGROUND

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, McLaren were the dominant force in Formula 1.

Between 1984 and 1991, the English team secured six Constructor’s and seven Driver’s Championships while the 1988 season saw them win an unprecedented 15 out of 16 races.

Discussions about a McLaren supercar first took place after the Italian Grand Prix in September 1988.

The plan was officially approved in early 1989.

The design team was led by Gordon Murray who had been the architect of both McLaren and formerly Brabham's Grand Prix success. Arguably the greatest Formula 1 designer of his generation, Murray was the driving force behind the McLaren road car and almost single-handedly convinced team boss, Ron Dennis, to back it.

Pitched as the ultimate road car, Murray’s concept was for a light weight, high-powered machine that employed the latest Formula 1 technology. It would use a naturally aspirated V10 or V12 engine, a carbon composite monocoque and a three-seat layout with the driver positioned ahead of a passenger on either side.

The resultant McLaren F1 was unveiled in prototype form at the Monaco Grand Prix in May 1992.

The first production car was delivered 18 months later in December 1993.

Theoretically a rival for the Bugatti EB110 SS (£330,000), the Jaguar XJ220 (£470,000) and the soon-to-be-replaced Ferrari F40 (£197,000), in reality, the £640,000 McLaren raised the bar to a completely new level.

Despite total production only reaching 106 units, no less than six different F1 variants were manufactured.

There was the standard road car of which 69 were completed including five prototypes. Three types of racing F1 GTR were also made (28 built) plus the LM and long-tailed GT homologation specials (six and three built respectively).

Extraordinarily, McLaren lost money on every F1 they sold; the car was built without regard to cost and every aspect bristled with innovation.

CHASSIS

Like the Bugatti EB110, the F1 was built around a carbon composite monocoque. Incredibly light and strong, but also very expensive to produce, this state-of-the-art chassis helped the new McLaren exceed the most stringent safety regulations by some considerable margin.

Suspension was via double wishbones formed from solid aluminium alloy.

At the front, McLaren’s Ground-Plane Shear Centre featured unequal-length double wishbones that supported a machine cast-aluminium hub carrier. Each front suspension wishbone was connected to a subframe via plain bearings. The frame itself was four-point mounted to the carbon monocoque via purpose-designed elastomeric bushes.

Rear suspension loadings were fed via the transaxle and engine assembly into the central monocoque with drive and braking loads accepted via axially rigid bulkhead mountings. Torsional loads were absorbed via Inclined Shear Axis mounts into the shoulder beams each side of the engine.

Aluminium alloy was also used for the lightweight monotube gas-pressurised dampers produced specially for McLaren by Bilstein.

An anti-roll bar was installed at the front only.

This state-of-the-art suspension set up provided almost faultless ride and drive dynamics.

Brembo supplied the unassisted cross-drilled and ventilated brake discs. They had a 332mm diameter at the front and 305mm diameter at the rear.

Carbon discs were considered, but they were ultimately ruled out in favour of steel as the new technology was not considered mature enough for road use.

Four-piston Brembo monobloc calipers were another first for a road car; they were machined from a single piece of solid aluminium as opposed to the conventional approach where two-piece calipers were bolted together.

OZ Racing manufactured the five-spoke centre-lock wheels. Formed in magnesium, they had a 17-inch diameter and measured 9-inches wide at the front and 11.5-inches wide at the rear. Goodyear and Michelin both developed custom tyres for the car.

A 90-litre fuel tank was positioned between the driver’s seat and the engine.

ENGINE / TRANSMISSION

Engine-wise, nothing other than a large displacement normally-aspirated V10 or V12 was ever considered.

As Honda were McLaren’s engine supplier in Formula 1, it initially seemed likely the Japanese firm would develop a powerplant.

However, when Honda refused, Murray turned to BMW’s Paul Rosche. Murray and Rosche had previously worked together during Brabham and BMW’s successful Formula 1 partnership between 1982 and 1985.

McLaren required an engine with at least 550bhp, a maximum 600mm block length and a weight no heavier than 250kg.

BMW’s Motorsport department obligingly created a 6.1-litre V12 by late 1991.

Designated Type S70/2, the spectacular dry-sumped 60° V12 featured dual chain-driven overhead camshafts for each bank of cylinders, four valve cylinder heads and variable valve timing.

Aluminium alloy was used for the block and heads with magnesium for the cam carriers, cam covers, oil sump, dry sump and camshaft housings.

Intake control was via twelve individual butterfly valves while operation of the continuously variable camshafts was based on BMW’s VANOS system.

Each cylinder used twin fuel injectors managed by sophisticated TAG software.

Displacement was 6064cc thanks to a bore and stroke of 86mm and 87mm respectively.

The compression ratio was set at 11.0:1.

Peak output was 627bhp at 7500rpm and 479lb-ft at 5600rpm.

Although BMW’s Type S70/2 engine came out 16kg heavier than requested (266kg), the 6.4% weight increase was offset by peak output exceeding the original 550bhp target by 11.4%.

The engine doubled as a load-bearing chassis member. It was mounted against the rear cockpit bulkhead and attached to two monocoque shoulder beams at the rear.

16 grams of gold were famously used to line the engine bay as this was the best heat insulating material available.

Transmission was via an AP triple-plate carbon clutch with an aluminium flywheel, a Torsen limited-slip differential with 40% lock and a transversely mounted six-speed manual gearbox developed with Traction Products of Costa Mesa, California. The gearbox was housed in an aluminium alloy casing.

BODYWORK

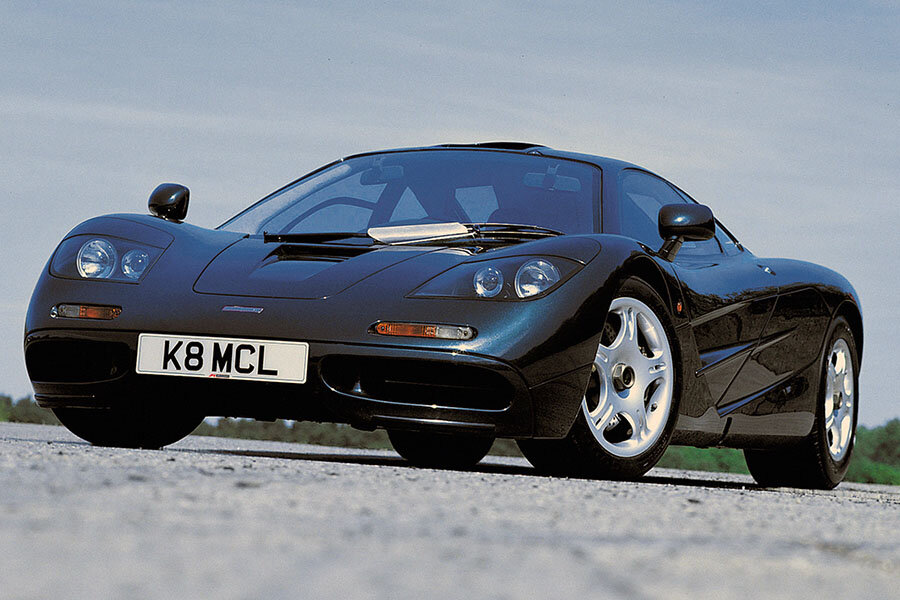

A styling team led by Peter Stevens designed the bodywork; the result was uncompromised aerodynamic efficiency with well-balanced proportions and elegant lines.

Unconventionally styled, the body was formed wholly in carbon composite.

It featured dihedral butterfly doors, distinctive brake cooling ducts each side of the nose and a roof-mounted intake that directed high pressure air into the engine.

As luggage was to be concealed behind opening storage panels down each flank, the F1 was able to adopt an unusually short rear overhang.

There were no fixed wings, just an electronic rear spoiler that automatically adjusted under heavy braking to balance the centre of gravity. When activated (by brake line pressure at speeds over 40mph), the spoiler flipped up to reveal two ducts that directed air towards the rear brakes.

The rear deck and fascia were extensively louvred to release engine and exhaust gasses. Intakes located on each door cooled the oil tank and electronics.

For the first time on a road car, full ground-effect aerodynamics were employed which helped explain the F1’s ultra clean profile. Underneath was a rear diffuser to increase downforce. There were also a pair of electric Kevlar fans that reduced pressure beneath the car. These fans directed the air through the engine bay for additional cooling.

INTERIOR

Inside, the F1’s vast windscreen and generous side windows gave unusually good visibility for such a high performance car.

The 1+2 cockpit layout featured a carbon composite seat moulded to the owner. Driver and passenger seats were trimmed in the thinnest available leather which, like the carpet, was supplied by Connolly.

Directly behind the non-airbag three-spoke steering wheel was a curvaceous binnacle that housed all the instrumentation and some of the switchgear. A central 8000rpm rev counter was flanked to the right by a 260mph / 400kph speedometer and to the left by a combined read out for fuel, oil pressure and water temperature. There was also an array of warning lights plus two digital read outs linked to the on board computer.

A trio of toggle switches were located either side of the binnacle. The remaining switchgear was housed on central control panels either side of the driver.

Standard equipment included air-conditioning, electric windows, a special lightweight Kenwood stereo with ten CD shuttle, a titanium Facom toolkit and tailored luggage.

OPTIONS

Mid-way through production, a High Downforce Kit that comprised GTR body parts and wheels was offered as an optional extra.

WEIGHT / PERFORMANCE

With 627bhp in an 1140kg package, the F1 set new performance standards.

Its acceleration figures were astounding; 0-62mph took 3.2 seconds, 0-100mph took 6.3 seconds and 0-150mph took 12.8 seconds.

The car’s top speed wasn’t finally established until 1998 when McLaren took chassis XP5 to Volkswagen’s Ehra-Lessien test track in Germany and hit 241mph.

PROTOTYPES

A full-scale clinic model was unveiled at the Monaco Grand Prix on May 28th 1992.

Five operational prototypes followed, the first of which was completed in December 1992.

PRODUCTION

The first of 64 production cars (chassis 002) was finished in December 1993.

The last (chassis 075) was completed in mid 1998.

Text copyright: Supercar Nostalgia

Photo copyright: McLaren - https://www.mclaren.com